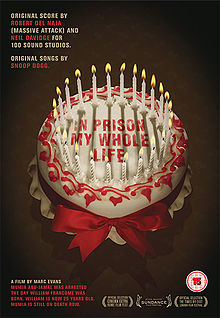

Interview with William Francome, writer of ‘In Prison my Whole Life’

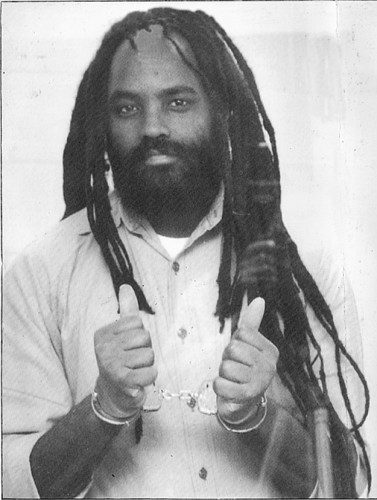

After our screening of  ‘In Prison all my life’, I spoke to film-maker and writer William Francome about what happened to Mumia Abu-Jamal, issues of racial tension in the US and his new project ‘The Penalty’ that will be starting raising money on Kickstarter on 6th November and looks to be released in early 2016.

Â

RC: I understand that Mumia’s death sentence was revoked after the film was released, can you bring me up to date on what’s happened?

WF: While we were making the film was being made his death sentence was vacated but he had to stay  on death row because the state pulled an appeal to keep him on death row. After the filming it finally went through the courts and his death sentence was vacated. In America you have two phases of a trial in a death penalty case, you have a  guilt phase and a sentencing phase. He is still considered guilty of the crime but not sentenced to death. So he is still imprisoned for life without the possibility of parole, so he will still stay in prison until he dies of old age and he has no chance of getting out, currently.

RC: You mentioned that he has a limited chance of getting out or a free trial still, why is this?

WF: It is very difficult to appeal court cases in America. I feel myself that there were some serious issues within his case, but the courts have essentially said that they do not feel that is the case. You have to prove that a certain fact would have been strong enough that it would have swayed a jury one way or the another. That’s not the easiest thing to do, it’s often conceptual. In Mumia’s case the judge, in his PCRA (Post Conviction Relief Act) hearing, came out of retirement  specially to hear the case – the same judge that had heard his case in the beginning. Considering one of the main issues of him having a fair trial, was the bias of the judge, it was kind of ridiculous to have the same judge. I know that Mumia was hopeful that he would get a new trial, that’s where we left the film, we thought he might get one and in the end he didn’t. While he is no longer on death row, he still feels like he is serving a death sentence, he still considers it to be a travesty and that he is innocent and that if he had his day in court  he would have been able to get his fair trial that we didn’t think he had and that Amnesty don’t think he had. Whether he shot the policeman or not, I don’t know but what I do know is that he didn’t have a fair trial.

RC: What was the experience of making ‘In Prison All My Life’, was it a big learning curve?

WF: Yes definitely, I was at university when I wrote down the idea for the first time. Originally I had written this idea for a film and no one was interested, my sister was working at ITV and she pitched it there and to some other people and I kind of gave up on the idea. Two years later my girlfriend Katie was like, ‘let’s do this’ and then we decided we were going to do it. We got very lucky, Colin Firth and his wife Lydia got involved, they heard about what we were doing and they wanted to help us do it. It was a fantastic experience, it was very stressful and it was a learning curve but we had some fantastic people on board and some people who were really dedicated to making this film and to letting me have this vision and go on this journey. I was able to go off and meet these people and ask the questions I wanted to ask.

RC: Do you think things have progressed in the US or does it appear to be quite stagnant?

WF: I do definitely think things are changing, I think now we are seeing a level of debate around the death penalty that we have never seen before. Mumia’s case was the loudest and it was the most famous in the late 90s, in 1998 you had a 80% approval rate of the death penalty in the US but now it’s down to 53/54%. That is a huge swing in twenty years, a significant 30%,  and I think a lot of that is to do with exoneration particularly DNA exoneration. I think that people are understanding, ‘well god if there’s one innocent person than that’s probably one too many and how much is it costing us?’ I think that people have pretty much acknowledged that it costs almost three times as much to have someone on death row and to executed than to leave them in prison for life.  I think that the general public is understanding a lot more, I can definitely tell that there is a shift and once you get to a point when you’re around 50% then it’s time to think that it is a fundamental issue in society  and surely we should look for a unanimous rather than a case of 50% either way.

RC: 53% still seems quite high, why do you think this is?

WF: I think there is all sorts of historical situations and reasons, I also think popular support in the UK is probably not as far off that as you think. I think people in America think that it is appropriate for people who have done horrendous things. I am not going to tell people what they should or should not agree with it. I think people think the death penalty is quite often an abstract thought of ‘someone deserves to die for doing this horrendous thing.’

When you actually explain to people, it costs this much money and this is how many people who have been found to be innocent, and the issues of getting a fair trial in America, (especially if you’re poor or you’re some sort of minority), I think having something like an execution as the ultimate punishment suddenly seems like quite a major thing and I think when people begin to understand that their abstract idea of the death penalty really changes.

RC: Do you think that getting a fair trial in the US is still a big issue?

WF: Yes totally, there are endless people who’ve been innocent ended up on death row and in every case you hear the same thing time and time again: ‘I had a bad attorney’, ‘I didn’t have enough money to put up a good defence’, ‘the cops were racist’, or ‘I falsely admitted after two days of interrogation’. We had are these same problems crop up over and over again. I think what we are seeing with the 1000 people that have been exonerated from the Innocent Project is not just exceptional cases, but that there was a massive problem with injustice. Most people clean out because they’re too terrified whether they’re guilty or innocent, if you’re facing 100 years in prison but are told that if you plead guilty you’ll get 10 years in prison then even if they’re not guilty you’ll still plead out. There are some serious serious issues with the American justice system. I’m not saying that it’s impossible to get a fair trial but I would not say it is a flawless system by any means.

RC: Do you think there is still a problem with racial prejudice in the US?

WF: Totally, I think there completely is. I think many of people wanted to see the election of Obama as America suddenly becoming this post-racial nation that had dealt with its’ race and history. But at the end of the day black men are still locked up in a way that is unprecedented in anywhere else in the world. We’re in a time where prison is a solution to a lot of society’s issues and people just get banged up to deal with whole sections of society. I think particularly in poor urban nations, policing is a completely different situation. For young black males, their experience of the criminal justice system is totally different to what I would have got as a young white teenager growing up in suburban America. I think those issues are still definitely there, even though we have elected a black president and the odd people who can surpass the issues the wider issue is still there. I think that it is very hard to change those, unless you really invest and change things through education, through policing, through jobs. Unless you tackle those issues you will see the same issues over and over again.

RC: Is lack of representation still a major issue?

WF: I think it’s a lack of equality on multiple levels. If you do not have a certain level of education, and your parents did not have access to a certain level of education so they did not have as good jobs so you then have the problem of poverty. This is very broad brush strokes, but say you have a lower level of health, and a lower life expectancy and you have less opportunities and access to jobs. And say you’re in an area where you have less access to jobs and you’re policed in a certain way because you’re considered to be more dangerous and scary than other parts of society. Whether that is by black or white police officers. I think it a multitude of issues that all get compounded together, the overall effect is still a very unequal society.

RC: Can you tell me a bit about your new film, more death penalty (!) what led you to continue with this topic?

WF: (Laughs) I promise this will be the last death penalty project! Last year, I drove across America with my co-director and a couple of producers  we made ten films on the road. (The project is called ‘One for Ten‘) They’re all online and are free to download. It was a project that we wanted to be open to the public and it to be as interactive as possible. However, after this we still had a few more questions and in this privileged position with these relationships we had made we wanted to do another project answering these questions. In America it seems to be a really important point with the death penalty, we’re approaching the 50% mark, and I think when you approach the 50% mark then we really should be talking about this a bit more deeply. So we wanted to make a film that answered all these questions.

RC: What is different about your new film?Â

WF: In this new film The Penalty, we are going to be talking to people about it from all sides, and we’re following three major characters. Â This one guy who was on death row and was released after 15 years and who has got his life back on track, a lawyer who is trying to prevent his client from being executed by one of these new drug cocktails, and the third and final story which we are still looking for which is a family who are waiting for the execution of a loved one. We really want to look at it from all sides and look at what the reasons are for having it and what the reasons are for not having it. We don’t want it to be a campaign piece saying this is what you should think, we really want people to ask themselves questions. We think people often think of the death penalty as an abstract term so the worst of the worst people who have done the most horrendous things. I think often that is not the case, and the reality is a lot more complex. We just want to show those people and ask them: ‘what do you think now?’ and is this the sort of society you want to live in.

[Further updates will be made with the rest of the interview! Another three/four questions to follow.]